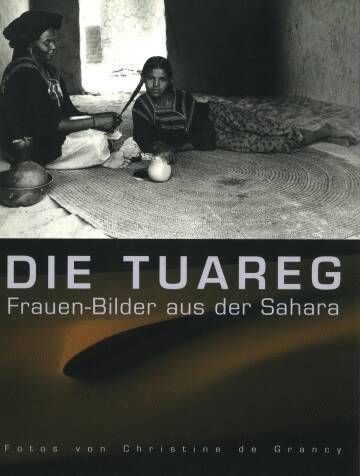

Tuareg Women

by Christine de Grancy

Photographs: Christine de Grancy

Publisher: Kulturverein Schloss Goldegg

128 pages

Year: 2000

ISBN: 9783901152078

Price: 44 €

Comments: soft cover

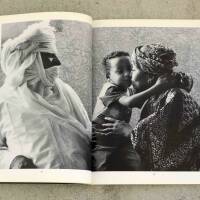

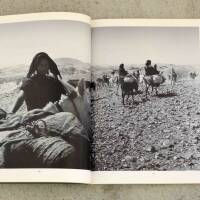

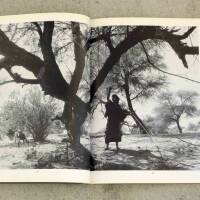

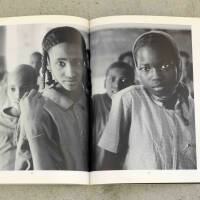

From 1984 to 1987 I got to know a smallish part of the Sahara; one in which a never-ending tragedy is taking place. I was working on a book on the lives of one of the endangered tribes in the world, the Sahraouis, in an Algerian refugee camp near Tindouf. The book was to deal with the freedom movement called Frente Polisario. With it's freedom fighters I managed to penetrate into their principal territory: the former colony of Spanish Western Sahara. Morocco has continually claimed this territory, and as a much stronger neighbour, lobbied for it's annexation to it's kingdom. The rest of the world has looked on in indifference as the Kingdom strips the territory of it's sovereignty. It was then that the appalling problems of the Tuaregs in Southern Algeria first came to my attention. In the refugee camps of the Sahraouis, situated in the inhospitable regions of Tindouf, the older women would tell stories about their former nomadic life, contrasting very strongly to their present life in the astonishingly well-organised refugee camps of the Sahraouis. Yet they displayed an iron will to return to their former existence. It was clear to them that, if were they to be given an own state, be it through fighting or tough negotiations, their nomadic lives would have to be altered dramatically. It is impressive how , having very scarce means at their disposal, these people try to adapt to the rhythm of modern life. With calculated steps they try to find a connection to the rest of the world, not letting go of their own traditions, even as refugees, instead, trying to continue a normal life. We Westerners and Europeans, having branded our own style of modernity for generations, can hardly keep up with what we have come to label progress. Our deep-rooted anxiety has been fundamentally destructive. We seem to have ventured out to the edge of the abyss. Oblomov, Iwan Gontscharow's controversial 19th century figure, makes us able and restless modern people see the core of the matter: ''.....we all infect each other with our agonising worries and ennui, all fervently seeking something. Behind this mask of activity lies our true lack of compassion and general emptiness.'' Through this lack of compassion we destroy the variety and richness of life itself, it's nature and the very human beings in their respective differences, which have evolved throughout thousands of years. Now we seem to strive for global unity, possibly the last colonisation of man as a free thinker. Global connection and streamlining of millions of people has become possible through new media and information technology. Western economies with their refined advertising and consumer strategies , tourism and multiple event spectacles all work like drugs to drive humanity into ultimate, possibly not unpeaceful, slavery. People's living conditions on this planet are still varied , sometimes extreme and their adaptability enormous. Let's take Tuareg women as an example, having experienced how they tend to their herds of goats, in correspondence, freedom and respect for the awesome nature of the Sahara desert is an unforgettable experience. To talk about the power and loss of this freedom alone is impossible, as we tend to use the word without really knowing it's deepest and truest meaning. Maybe there is a curse on the sedentary , always dishing up something stiff, monotonous and final, like an early death gnawing away at life. People, who are prepared to transcend the boundaries and risk freedom at each step develop a different perspective on life. On the contrary, those who are captive of their own lethargy, tend to be entirely without any joie de vivre, some of these have produced great prisons. For this reason, Tuareg women, as well as the Sahraouis, fear the rise of Fundamentalism in their vicinity. Until now , their free lifestyle guaranteed a high degree of respect for their husbands, for their freedom and self-worth. The Spanish-Arabic philosopher Averroes-Ibn Ruschd (1126-1198) , strongly influenced by Plato, criticised Muslim attitude to women.'' In our state, we have no idea what capacities women have, other than their reproductive function. For this we turn them into man's servant, to feed and raise children. This destroys whatever other quality is in them. Because women are not recognised as having any other human qualities, they are often compared to plants. The fact that she is seen to be nothing but a burden to man, explains why these states are so poor.'' The apparent matriarchal structure of the Tuaregs defies this. Generally speaking, one could assume that nomadic life in the Sahara necessarily requires alert partners, often having to decide together on survival strategies. This is encapsulated in a saying I picked up from the Sahraouis: ' We'll sleep only when we're dead.' One can still admire the beauty of their dignified walk. 'Targia' is the name for the light yet burdened steps of life. Generations have crossed the Sahara, as they have, searching for the absolutely necessary for their families and animals. Nothing more, nothing less. This taught me the true meaning of the word necessity.

> see also Christine de Grancy's fine art prints

More books by Christine de Grancy

-

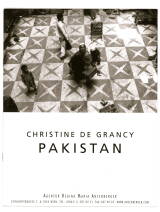

Pakistan (signed - last copy)

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 35 -

Lebenszeichen (signed)

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 85 -

Tausend und eine Spur

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 40 -

Die Sahraouis

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Chinesen

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Landschaft für Engel

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 80 -

Das Jahr ohne Widerruf

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Wandlungen - Ereignis Skulptur / Transfigurations - A Sculptur...

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 30 18.00 -

Hallodris und Heilige - Engel und Lemuren

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 45 -

Lebenszeichen

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 29 -

Erika Pluhar: Ein Bilderbuch

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 28 -

Sturm und Spiel. Die Theaterphotographie der Christine de Grancy

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 38

more books tagged »Morocco« | >> see all

-

Le Maroc, que j'aime...

by Louis-Yves Loirat

Euro 20 -

Ouarzazate (signed)

by Mark Ruwedel

sold out -

Marocains

by Daoud Aoulad-Syad

sold out -

Marrakech

by Daido Moriyama

sold out

more books tagged »Austrian« | >> see all

-

Ukraine

by Reiner Riedler

Euro 18 -

Photographica Auction 2010

by Westlicht

sold out -

East Coast - West Coast

by Alfred Seiland

sold out -

KRETA 2

by Kreta 2 Kollektiv

Euro 25 -

by the world forgot. Portraits of Indigenous Peoples of Asia (...

by Christoph Lingg

Euro 65 -

Photographica Auction 2017 (last copy)

by Westlicht

sold out

more books tagged » documentary« | >> see all

-

Manchester 1970s

by John Bulmer

sold out -

Man Next Door (signed - last copy)

by Rob Hornstra

sold out -

Der Parasit / The Parasite (signed)

by Sophie Tiller

Euro 59 -

British Rituals

by David Levenson

Euro 25 -

Son

by Christopher Anderson

sold out -

Ich war hier (signed)

by Andreas Frei

Euro 39

more books tagged »desert« | >> see all

-

ECHO

by Jungjin Lee

sold out -

Message from the Exterior

by Mark Ruwedel

Euro 55 -

Dona Maria and her Dreams (last two copies)

by Horst A. Friedrichs

Euro 75

more books tagged »black and white« | >> see all

-

Photographs (signed)

by Bruce Davidson

sold out -

History of the Visit (signed)

by Daniel Reuter

Euro 45 27.00 -

The Canadians

by Roger Hargreaves, Jill Offenbeck and Stefanie Petrilliv

sold out -

Human (signed - German edition - last copy)

by Gabor Arion Kudasz

sold out -

Italian Matters - Eclisse #2 (only 1 copy)

by Renato Abenavoli

Euro 95 -

Dark Knees

by Mark Cohen

sold out

more books tagged »Africa« | >> see all

-

THIS IS WHAT HATRED DID

by Cristina de Middel

Euro 66 -

Congo Democratic

by Guy Tillim

sold out -

A Sense of Common Ground

by Fazal Sheikh

Euro 69 -

Land Rover 1950s

by George Rodger

sold out -

The Borderlands

by Jo Ractliffe

sold out -

Nollywood (signed)

by Pieter Hugo

sold out

more books tagged »reportage« | >> see all

-

Andante (last copy)

by Alex Majoli

sold out -

The End of Manufacturing

by John Myers

Euro 25 -

Ferdinand Schmutzer - A Photographic Discovery (review copy)

by Regina Maria Anzenberger

Euro 75 60.00 -

Austrian Documentary Photography

by Regina Maria Anzenberger

Euro 75 -

Prestwich Mental Hospital 1972

by Martin Parr

Euro 85 -

Die grossen Fotografinnen

by various photographers

sold out

Random selection from the Virtual bookshelf josefchladek.com

Tuareg Women

by Christine de Grancy

Photographs: Christine de Grancy

Publisher: Kulturverein Schloss Goldegg

128 pages

Year: 2000

ISBN: 9783901152078

Price: 44 €

Comments: soft cover

From 1984 to 1987 I got to know a smallish part of the Sahara; one in which a never-ending tragedy is taking place. I was working on a book on the lives of one of the endangered tribes in the world, the Sahraouis, in an Algerian refugee camp near Tindouf. The book was to deal with the freedom movement called Frente Polisario. With it's freedom fighters I managed to penetrate into their principal territory: the former colony of Spanish Western Sahara. Morocco has continually claimed this territory, and as a much stronger neighbour, lobbied for it's annexation to it's kingdom. The rest of the world has looked on in indifference as the Kingdom strips the territory of it's sovereignty. It was then that the appalling problems of the Tuaregs in Southern Algeria first came to my attention. In the refugee camps of the Sahraouis, situated in the inhospitable regions of Tindouf, the older women would tell stories about their former nomadic life, contrasting very strongly to their present life in the astonishingly well-organised refugee camps of the Sahraouis. Yet they displayed an iron will to return to their former existence. It was clear to them that, if were they to be given an own state, be it through fighting or tough negotiations, their nomadic lives would have to be altered dramatically. It is impressive how , having very scarce means at their disposal, these people try to adapt to the rhythm of modern life. With calculated steps they try to find a connection to the rest of the world, not letting go of their own traditions, even as refugees, instead, trying to continue a normal life. We Westerners and Europeans, having branded our own style of modernity for generations, can hardly keep up with what we have come to label progress. Our deep-rooted anxiety has been fundamentally destructive. We seem to have ventured out to the edge of the abyss. Oblomov, Iwan Gontscharow's controversial 19th century figure, makes us able and restless modern people see the core of the matter: ''.....we all infect each other with our agonising worries and ennui, all fervently seeking something. Behind this mask of activity lies our true lack of compassion and general emptiness.'' Through this lack of compassion we destroy the variety and richness of life itself, it's nature and the very human beings in their respective differences, which have evolved throughout thousands of years. Now we seem to strive for global unity, possibly the last colonisation of man as a free thinker. Global connection and streamlining of millions of people has become possible through new media and information technology. Western economies with their refined advertising and consumer strategies , tourism and multiple event spectacles all work like drugs to drive humanity into ultimate, possibly not unpeaceful, slavery. People's living conditions on this planet are still varied , sometimes extreme and their adaptability enormous. Let's take Tuareg women as an example, having experienced how they tend to their herds of goats, in correspondence, freedom and respect for the awesome nature of the Sahara desert is an unforgettable experience. To talk about the power and loss of this freedom alone is impossible, as we tend to use the word without really knowing it's deepest and truest meaning. Maybe there is a curse on the sedentary , always dishing up something stiff, monotonous and final, like an early death gnawing away at life. People, who are prepared to transcend the boundaries and risk freedom at each step develop a different perspective on life. On the contrary, those who are captive of their own lethargy, tend to be entirely without any joie de vivre, some of these have produced great prisons. For this reason, Tuareg women, as well as the Sahraouis, fear the rise of Fundamentalism in their vicinity. Until now , their free lifestyle guaranteed a high degree of respect for their husbands, for their freedom and self-worth. The Spanish-Arabic philosopher Averroes-Ibn Ruschd (1126-1198) , strongly influenced by Plato, criticised Muslim attitude to women.'' In our state, we have no idea what capacities women have, other than their reproductive function. For this we turn them into man's servant, to feed and raise children. This destroys whatever other quality is in them. Because women are not recognised as having any other human qualities, they are often compared to plants. The fact that she is seen to be nothing but a burden to man, explains why these states are so poor.'' The apparent matriarchal structure of the Tuaregs defies this. Generally speaking, one could assume that nomadic life in the Sahara necessarily requires alert partners, often having to decide together on survival strategies. This is encapsulated in a saying I picked up from the Sahraouis: ' We'll sleep only when we're dead.' One can still admire the beauty of their dignified walk. 'Targia' is the name for the light yet burdened steps of life. Generations have crossed the Sahara, as they have, searching for the absolutely necessary for their families and animals. Nothing more, nothing less. This taught me the true meaning of the word necessity.

> see also Christine de Grancy's fine art prints

More books by Christine de Grancy

-

Pakistan (signed - last copy)

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 35 -

Lebenszeichen (signed)

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 85 -

Tausend und eine Spur

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 40 -

Die Sahraouis

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Chinesen

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Landschaft für Engel

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 80 -

Das Jahr ohne Widerruf

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Wandlungen - Ereignis Skulptur / Transfigurations - A Sculptur...

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 30 18.00 -

Hallodris und Heilige - Engel und Lemuren

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 45 -

Lebenszeichen

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 29 -

Erika Pluhar: Ein Bilderbuch

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 28 -

Sturm und Spiel. Die Theaterphotographie der Christine de Grancy

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 38

more books tagged »Morocco« | >> see all

-

Le Maroc, que j'aime...

by Louis-Yves Loirat

Euro 20 -

Ouarzazate (signed)

by Mark Ruwedel

sold out -

Marocains

by Daoud Aoulad-Syad

sold out -

Marrakech

by Daido Moriyama

sold out

more books tagged »Austrian« | >> see all

-

Ukraine

by Reiner Riedler

Euro 18 -

Photographica Auction 2010

by Westlicht

sold out -

East Coast - West Coast

by Alfred Seiland

sold out -

KRETA 2

by Kreta 2 Kollektiv

Euro 25 -

by the world forgot. Portraits of Indigenous Peoples of Asia (...

by Christoph Lingg

Euro 65 -

Photographica Auction 2017 (last copy)

by Westlicht

sold out

more books tagged » documentary« | >> see all

-

Manchester 1970s

by John Bulmer

sold out -

Man Next Door (signed - last copy)

by Rob Hornstra

sold out -

Der Parasit / The Parasite (signed)

by Sophie Tiller

Euro 59 -

British Rituals

by David Levenson

Euro 25 -

Son

by Christopher Anderson

sold out -

Ich war hier (signed)

by Andreas Frei

Euro 39

more books tagged »desert« | >> see all

-

ECHO

by Jungjin Lee

sold out -

Message from the Exterior

by Mark Ruwedel

Euro 55 -

Dona Maria and her Dreams (last two copies)

by Horst A. Friedrichs

Euro 75

more books tagged »black and white« | >> see all

-

Photographs (signed)

by Bruce Davidson

sold out -

History of the Visit (signed)

by Daniel Reuter

Euro 45 27.00 -

The Canadians

by Roger Hargreaves, Jill Offenbeck and Stefanie Petrilliv

sold out -

Human (signed - German edition - last copy)

by Gabor Arion Kudasz

sold out -

Italian Matters - Eclisse #2 (only 1 copy)

by Renato Abenavoli

Euro 95 -

Dark Knees

by Mark Cohen

sold out

more books tagged »Africa« | >> see all

-

THIS IS WHAT HATRED DID

by Cristina de Middel

Euro 66 -

Congo Democratic

by Guy Tillim

sold out -

A Sense of Common Ground

by Fazal Sheikh

Euro 69 -

Land Rover 1950s

by George Rodger

sold out -

The Borderlands

by Jo Ractliffe

sold out -

Nollywood (signed)

by Pieter Hugo

sold out

more books tagged »reportage« | >> see all

-

Andante (last copy)

by Alex Majoli

sold out -

The End of Manufacturing

by John Myers

Euro 25 -

Ferdinand Schmutzer - A Photographic Discovery (review copy)

by Regina Maria Anzenberger

Euro 75 60.00 -

Austrian Documentary Photography

by Regina Maria Anzenberger

Euro 75 -

Prestwich Mental Hospital 1972

by Martin Parr

Euro 85 -

Die grossen Fotografinnen

by various photographers

sold out

Random selection from the Virtual bookshelf josefchladek.com

Tuareg Women

by Christine de Grancy

Photographs: Christine de Grancy

Publisher: Kulturverein Schloss Goldegg

128 pages

Year: 2000

ISBN: 9783901152078

Price: 44 €

Comments: soft cover

From 1984 to 1987 I got to know a smallish part of the Sahara; one in which a never-ending tragedy is taking place. I was working on a book on the lives of one of the endangered tribes in the world, the Sahraouis, in an Algerian refugee camp near Tindouf. The book was to deal with the freedom movement called Frente Polisario. With it's freedom fighters I managed to penetrate into their principal territory: the former colony of Spanish Western Sahara. Morocco has continually claimed this territory, and as a much stronger neighbour, lobbied for it's annexation to it's kingdom. The rest of the world has looked on in indifference as the Kingdom strips the territory of it's sovereignty. It was then that the appalling problems of the Tuaregs in Southern Algeria first came to my attention. In the refugee camps of the Sahraouis, situated in the inhospitable regions of Tindouf, the older women would tell stories about their former nomadic life, contrasting very strongly to their present life in the astonishingly well-organised refugee camps of the Sahraouis. Yet they displayed an iron will to return to their former existence. It was clear to them that, if were they to be given an own state, be it through fighting or tough negotiations, their nomadic lives would have to be altered dramatically. It is impressive how , having very scarce means at their disposal, these people try to adapt to the rhythm of modern life. With calculated steps they try to find a connection to the rest of the world, not letting go of their own traditions, even as refugees, instead, trying to continue a normal life. We Westerners and Europeans, having branded our own style of modernity for generations, can hardly keep up with what we have come to label progress. Our deep-rooted anxiety has been fundamentally destructive. We seem to have ventured out to the edge of the abyss. Oblomov, Iwan Gontscharow's controversial 19th century figure, makes us able and restless modern people see the core of the matter: ''.....we all infect each other with our agonising worries and ennui, all fervently seeking something. Behind this mask of activity lies our true lack of compassion and general emptiness.'' Through this lack of compassion we destroy the variety and richness of life itself, it's nature and the very human beings in their respective differences, which have evolved throughout thousands of years. Now we seem to strive for global unity, possibly the last colonisation of man as a free thinker. Global connection and streamlining of millions of people has become possible through new media and information technology. Western economies with their refined advertising and consumer strategies , tourism and multiple event spectacles all work like drugs to drive humanity into ultimate, possibly not unpeaceful, slavery. People's living conditions on this planet are still varied , sometimes extreme and their adaptability enormous. Let's take Tuareg women as an example, having experienced how they tend to their herds of goats, in correspondence, freedom and respect for the awesome nature of the Sahara desert is an unforgettable experience. To talk about the power and loss of this freedom alone is impossible, as we tend to use the word without really knowing it's deepest and truest meaning. Maybe there is a curse on the sedentary , always dishing up something stiff, monotonous and final, like an early death gnawing away at life. People, who are prepared to transcend the boundaries and risk freedom at each step develop a different perspective on life. On the contrary, those who are captive of their own lethargy, tend to be entirely without any joie de vivre, some of these have produced great prisons. For this reason, Tuareg women, as well as the Sahraouis, fear the rise of Fundamentalism in their vicinity. Until now , their free lifestyle guaranteed a high degree of respect for their husbands, for their freedom and self-worth. The Spanish-Arabic philosopher Averroes-Ibn Ruschd (1126-1198) , strongly influenced by Plato, criticised Muslim attitude to women.'' In our state, we have no idea what capacities women have, other than their reproductive function. For this we turn them into man's servant, to feed and raise children. This destroys whatever other quality is in them. Because women are not recognised as having any other human qualities, they are often compared to plants. The fact that she is seen to be nothing but a burden to man, explains why these states are so poor.'' The apparent matriarchal structure of the Tuaregs defies this. Generally speaking, one could assume that nomadic life in the Sahara necessarily requires alert partners, often having to decide together on survival strategies. This is encapsulated in a saying I picked up from the Sahraouis: ' We'll sleep only when we're dead.' One can still admire the beauty of their dignified walk. 'Targia' is the name for the light yet burdened steps of life. Generations have crossed the Sahara, as they have, searching for the absolutely necessary for their families and animals. Nothing more, nothing less. This taught me the true meaning of the word necessity.

> see also Christine de Grancy's fine art prints

More books by Christine de Grancy

-

Pakistan (signed - last copy)

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 35 -

Lebenszeichen (signed)

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 85 -

Tausend und eine Spur

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 40 -

Die Sahraouis

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Chinesen

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Landschaft für Engel

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 80 -

Das Jahr ohne Widerruf

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 60 -

Wandlungen - Ereignis Skulptur / Transfigurations - A Sculptur...

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 30 18.00 -

Hallodris und Heilige - Engel und Lemuren

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 45 -

Lebenszeichen

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 29 -

Erika Pluhar: Ein Bilderbuch

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 28 -

Sturm und Spiel. Die Theaterphotographie der Christine de Grancy

by Christine de Grancy

Euro 38

more books tagged »Morocco« | >> see all

-

Le Maroc, que j'aime...

by Louis-Yves Loirat

Euro 20 -

Ouarzazate (signed)

by Mark Ruwedel

sold out -

Marocains

by Daoud Aoulad-Syad

sold out -

Marrakech

by Daido Moriyama

sold out

more books tagged »Austrian« | >> see all

-

Ukraine

by Reiner Riedler

Euro 18 -

Photographica Auction 2010

by Westlicht

sold out -

East Coast - West Coast

by Alfred Seiland

sold out -

KRETA 2

by Kreta 2 Kollektiv

Euro 25 -

by the world forgot. Portraits of Indigenous Peoples of Asia (...

by Christoph Lingg

Euro 65 -

Photographica Auction 2017 (last copy)

by Westlicht

sold out

more books tagged » documentary« | >> see all

-

Manchester 1970s

by John Bulmer

sold out -

Man Next Door (signed - last copy)

by Rob Hornstra

sold out -

Der Parasit / The Parasite (signed)

by Sophie Tiller

Euro 59 -

British Rituals

by David Levenson

Euro 25 -

Son

by Christopher Anderson

sold out -

Ich war hier (signed)

by Andreas Frei

Euro 39

more books tagged »desert« | >> see all

-

ECHO

by Jungjin Lee

sold out -

Message from the Exterior

by Mark Ruwedel

Euro 55 -

Dona Maria and her Dreams (last two copies)

by Horst A. Friedrichs

Euro 75

more books tagged »black and white« | >> see all

-

Photographs (signed)

by Bruce Davidson

sold out -

History of the Visit (signed)

by Daniel Reuter

Euro 45 27.00 -

The Canadians

by Roger Hargreaves, Jill Offenbeck and Stefanie Petrilliv

sold out -

Human (signed - German edition - last copy)

by Gabor Arion Kudasz

sold out -

Italian Matters - Eclisse #2 (only 1 copy)

by Renato Abenavoli

Euro 95 -

Dark Knees

by Mark Cohen

sold out

more books tagged »Africa« | >> see all

-

THIS IS WHAT HATRED DID

by Cristina de Middel

Euro 66 -

Congo Democratic

by Guy Tillim

sold out -

A Sense of Common Ground

by Fazal Sheikh

Euro 69 -

Land Rover 1950s

by George Rodger

sold out -

The Borderlands

by Jo Ractliffe

sold out -

Nollywood (signed)

by Pieter Hugo

sold out

more books tagged »reportage« | >> see all

-

Andante (last copy)

by Alex Majoli

sold out -

The End of Manufacturing

by John Myers

Euro 25 -

Ferdinand Schmutzer - A Photographic Discovery (review copy)

by Regina Maria Anzenberger

Euro 75 60.00 -

Austrian Documentary Photography

by Regina Maria Anzenberger

Euro 75 -

Prestwich Mental Hospital 1972

by Martin Parr

Euro 85 -

Die grossen Fotografinnen

by various photographers

sold out

Random selection from the Virtual bookshelf josefchladek.com